Originally posted on Archetype Mirror

Written by Katie Chiou

I recently wrote a post on my personal blog about the state of the music industry, spanning the economics of streaming to social discovery to the role of media publications in elevating artists. The general thesis was that the music ecosystem is extremely complex and esoteric, and we’re overdue for new models and new platforms.

The original post was not framed through the lens of solution-finding or crypto, but my research made me more excited and confident about the opportunity for crypto to enable next-generation social platforms and creator tooling.

So far, explorations in onchain social and creator platforms emerge from the following guiding question: “Should I build for web2 users or should I build for crypto-native users?” Consequently, a tension between two approaches arises–familiar and arguably skeuomorphic platforms like Lens or Farcaster vs. more experimental, “crypto-native” platforms like Friend.tech or Song.tech that are often explicitly financially speculative.

Rather than argue that one approach is better than the other, I’d like to explore the potential of onchain social through a different first principles question: “What types of platforms uniquely leverage the power of being onchain?”

To properly understand the “power of being onchain,” we must return to what I’ll call “The Principles of Onchainness,” drawing heavily from Jacob Horne’s seminal piece “Onchain,” and examine how onchain mechanisms can unlock net-new platforms and features for users, builders, and creators.

Permissionless + Composable

The permissionless nature of blockchains means anyone can participate onchain without requiring approval or permission from any central authority or platform. The public and open anatomy of the network also means that everyone has access to all existing onchain data and, consequently, onchain users.

Composability closely follows being permissionless. Permissionless composability is a strong value proposition for builders who can now build apps and interfaces on top of existing data and protocols–tapping natively into social graphs, media, assets, etc. without necessarily having to bootstrap data or users from scratch or acquire permissions from any closed ecosystem or API economy. An important aside is the ability to do this while maintaining user privacy and integrity through cryptographic mechanisms such as ZK.

From Chris Dixon:

“When Twitter changed their API in 2011 or so, there was a big wave of startups — including a lot of my friends — who built Twitter startups. That was a thing in 2009 and 2010, with Tweety, TweetDeck, and all sorts of API services. [...] at some point [Twitter] decided, ‘Hey, we need to control. We are going to have client software, have an ad-based model, and change the API,’ and that whole industry died. Same thing happened with the Facebook platform.”

Composability breeds developer innovation, but what does “permissionless” or “composable” actually mean to the average user?

Users don’t join platforms out of principle, they join for some sort of utility (whether social, economic, emotional, etc.). Web2 consumer social platforms, for obvious reasons, make it nearly frictionless for users to join, making the immediate utility of a “permissionless” platform perhaps non-obvious. Composability is only valuable for users insofar as if there’s another platform or app users want to use, they don’t necessarily have to start building their social graphs or assets or even log history from zero.

From Eugene Wei when initially reviewing this post:

“The example I like to use is that every app that wants social features forces people to go through a friend discovery process and to build their network from scratch (Netflix and other social viewing experiences, for example). But scaled services like that probably already have enough nodes for a scaled graph, it's just the friction to create the graphs again that prevents us from experiencing what a social version of that service would be.”

At its weakest, onchain composability can eliminate the possibility for user data to be locked into a single platform. Threads is an example of unsuccessful composability, where the platform was able to attract signups at mind-blowing speed due to its native integration with Instagram, but quickly lost the majority of its daily active users because the Threads experience was not considered fun or differentiated.

At its strongest, symbiotic platform relationships can actually incentivize users to traverse platforms. When I think about a rich digital social ecosystem, the first example that always comes to mind is Neopets. Imagine a world in which every spot on the map–whether a game, store, quest, battle, etc.–was built permissionlessly by a different team, each not knowing the other, leveraging the same universal player data and identity. These types of open, interoperable world-building experiences are not possible in web2 where data access is constrained to a single team or permissioned access.

Ownership + Autonomy

Ownership is probably the most straightforward value proposition of onchainness. In web3, whatever you own onchain, you own everywhere, forever.

However, knowing when ownership is a must-have versus a nice-to-have is crucial when designing a consumer experience–and the answer is more complicated than one might think. While the value of onchain ownership is usually discussed in the context of owning assets themselves, this neglects a far bigger picture.

For the sake of this post, we can think about ownership in two different, often interlocking, forms: owning assets and owning distribution.

Owning an asset is important when it has persistent, long-term value–money, art, “real-world” assets or representations of such. These assets have clear utility, aesthetic value, and/or durable markets. Owning assets onchain is usually most important in the context of security, ensuring that these high-value assets are secure, self-custodied, and can’t be siphoned away from the user.

Owning distribution is important when the assets themselves either aren’t objectively valuable or are only valuable within a specific context. To extend the earlier Instagram/Threads example, if Instagram suddenly shut down tomorrow, all my posts would disappear. How much does this matter? I may care about my posts emotionally, but I could very easily save the pictures in other places (like a hard drive). However, losing Instagram as a distribution channel for my pictures means Iosing 1) the social context in which my pictures became valuable, 2) the social graph/audience I crafted from the platform, and 3) history/proof that I was ever on the platform at all. This is a similar case for Twitter. If I were really that attached to my tweets, I could just screenshot them or write them down. I can even still download all my Twitter data (though this feature is permissioned/could be killed at any time). However, losing access to Twitter as a platform would mean losing access to my audience, my distribution, and the years of history and social capital I’ve accumulated from using the platform.

Owning distribution can be just as, if not more, valuable than owning an inherently valuable asset. Distribution → social capital → economic capital is often a powerful revenue flywheel for creators, with the monetization features either baked into the platform directly (YouTube) or indirectly (Instagram + brand partnerships).

As a holistic, real-life example, take this Reddit post from a DistroKid user. For level-setting, DistroKid is a creator platform that allows artists to upload their music to streaming platforms like Spotify and Apple Music and manage their streams earnings across those platforms.

In this example, it’s important to recognize that the music files themselves aren’t the issue, it’s the distribution and revenue tied to the uploads, facilitated by DistroKid. Without DistroKid, the artist has little clarity or control over their uploads, their metrics on streaming platforms, and the revenue they’ve accrued and are due. There are other platforms similar to DistroKid like TuneCore and CD Baby that artists can switch to, but interoperating between these platforms is a whole new challenge in itself. This isn’t to say that platforms like DistroKid are inherently bad, power structures simply exist in a web2 ecosystem that give platforms indiscriminate control.

In an onchain ecosystem, while the artist may still interact with a DistroKid-like interface, they’d have much more autonomy. They would be able to directly check and manage their assets onchain, the value accrued to those assets could flow programmatically through the protocol, and the artist can directly view and interact with their onchain audience. DistroKid wouldn’t be able to arbitrarily change the mechanics of the underlying protocol without being held publicly accountable–platforms are more incentivized to maintain credible neutrality.

The amount of autonomy an “onchain DistroKid” exactly enables still depends on many core design decisions, but at the very least the mechanics of the platform would be much more transparent to its users. If the interface becomes untrustworthy or a “bad actor,” the public is able to keep entities accountable and/or another interface could directly compete while leveraging the same data.

A few onchain-specific features to highlight that also strengthen ownership:

Protocols: Protocols enable distribution channels, social graphs, and transaction history to be permanent and programmable. Even if a platform shuts down, the underlying protocol keeps all the data, assets, and rules intact allowing other interfaces to easily emerge.

Markets: Onchainness makes it simple to permissionlessly create markets around assets, thereby making those assets more attractive to own. We’ve seen examples of consumer social platforms creating markets for their native assets in attempts to make them more durable and objectively valuable. For example, Friend.tech keys only have utility in the context of Friend.tech as a platform, but the markets around keys make them more valuable as singular assets.

Provenance

To date, provenance has been one of the more legible and compelling value propositions of being onchain to artists and creators.

In a world of 1) digital nativity and transmission, 2) permissionless remixing, and 3) synthetically-generated content, tracking authorship and attribution becomes a significant challenge.

Josh Benaron, the founder of Bundlr, describes this problem space well:

“In the Web2 era, internet users gained the ability to easily ‘write’ to the internet. While this empowered users in new ways, the explosion of content came with downsides: murky attribution, lack of metadata to describe the content, unverifiable authorship, and weak assurances around who created content and when. AI has only magnified these downsides with its ability to facilitate counterfeit and derived content at a scale never before imagined. This trajectory sets us on a collision course where inaction will have grave consequences.”

A few real-world examples:

-

In an interview with the CEO of YouTube, creators Colin and Samir (1.4M subscribers) share that the most popular Colin and Samir videos on YouTube are short clips of their original videos posted by third parties. Colin and Samir aren’t able to capture any direct view count metrics or AdSense revenue from these videos, even though they created the original content. YouTube has a system called Content ID and a newer tool called Remix that were created to better attribute value to original creators, but the systems are not highly sensitive or yet used, respectively. Colin and Samir have resigned to the fact that the shorts (hopefully) give them free distribution.

-

TikTok has created an entirely new way to discover, distribute, and trial songs. Artists often have to scramble to funnel the free distribution into ways that actually capture monetary value. For example, in 2020 Aly and AJ released a new, explicit version of their 2007 song “Potential Breakup Song” after the original song went viral on TikTok. According to an article from Variety, “the TikTok trend associated with ‘Potential Breakup Song’ led to the creation of about two million videos, with the two most popular posts collecting over 10 million likes each.” The re-released version has amassed over 50M streams on Spotify, as compared to the original which has about 150M Spotify streams.

-

Ghostwriter is a music artist known for creating songs with AI-generated vocals from artists like Drake and the Weeknd, gaining 15M+ views on TikTok for their song “Heart on My Sleeve.” Neither Drake nor the Weeknd were directly compensated for the usage of their vocals, and neither have publicly commented on Ghostwriter’s music.

Derivatives have been valuable art forms since the beginning of art itself (remixing, sampling, interpolation, etc.), and attempting to terminate those artforms is a losing battle. However, as content becomes digitally-native and the technical barrier to creating and distributing digital-native content plummets to zero, the context collapse around remixed content becomes an existential issue. Authorship and authenticity are crucial to creators and artists who want to capture the full value of their work, whether as social capital or economic capital.

Verifiable provenance makes the transfer of content between people and platforms seamless.

“By being onchain, information gets a provable provenance that establishes its origins, its collaborators and supporters, and its context in a way that’s permanently and publicly accessible without requiring any institutional stamp of approval or maintenance. This system of independent verification and dissemination of knowledge—whether it be ideas, artwork, or personal information—is truly revolutionary.”

- Yancey Strickler, Co-Founder of Kickstarter, Co-Founder of Metalabel

As technical barriers fall and tools/platforms launch unique ways for users to leverage AI, the social inclination to interact with these applications increases. However, today’s younger users are also both more socially conscious and emotionally attached to artists, meaning they are simultaneously less willing to engage with platforms and tools perceived as extractive.

For derivative, remixed, or synthetically-generated content to truly reach its mass potential, value from these platforms must tangibly flow back to artists. Value doesn’t have to be explicitly financial, but cultural capital often indirectly leads to financial capital, though the relationship is quite blurred. Being able to at least map these flows more distinctly becomes even more of a priority.

Coordination

Being able to track information between people is just as much a coordination issue as it is a source issue. Programmatic provenance increases the speed and granularity at which information and data can move.

In abstract terms, this means that 1) the upper limit of people that can be coordinated simultaneously disappears, 2) the number of layers added onto a piece of media or information (remixing) without losing context approaches infinity, and 3) the atomic unit of information or value that can be transferred between people or platforms approaches zero.

What does this actually unlock? I’ve shared this before when writing about the type of future I’m excited to watch crypto enable:

Communities to self-organize and govern

Communities to self-custody, coordinate, and deploy capital

Users to own and selectively share/their identity/data

Strong coordination mechanisms create environments in which people are actually rewarded for collaboration, rather than zero-sum mechanisms. We see this clearly with the rise of freelance workers and experimentation around DAOs. From a 2021 post I originally wrote in collaboration with Station called “A New Genre of Work”:

“In his seminal 1937 essay, The Nature of the Firm, economist Ronald Coase explained why companies exist—to reduce the friction and transaction costs of contracting individual work on the free market. While perhaps a truth of the past, traditional corporations with bloated management and poor incentives for employees and users no longer effectively create value. Rather than focusing on practicing the craft at hand, tremendous energy is wasted optimizing for zero-sum games of equity vesting, salary negotiation, and organizational politics. [...] It’s clear that the most thorny problems facing humanity today—climate crisis, cybersecurity, income inequality to name a few—will not be solved by one corporation or one individual. These problems need to be addressed with the scale and efficiency of a corporation, without compromising on individual autonomy, creativity, and ownership. They require fluid and multidisciplinary collaboration that transcends the borders of institutions, from corporations to nation-states.”

With onchain mechanisms, networks can be orchestrated programmably, and value can stream atomically to contributors. Inherently decentralized fields like AI and media, that are rapidly approaching and inevitable, can be better approached from positions of encouragement, rather than fear.

The Power of Onchain: 1 + 1 = 3

Permissionless, Composable, Ownership, Autonomy, Provenance, Coordination

It’s worth examining how these lofty principles can actually be stitched together to unlock new, rich experiences.

The permissionless and composable principles of blockchains realistically benefit builders and developers more than they do end users. Think of this similarly to a perhaps more self-evident statement that users don’t care if the AI they’re interacting with was built with an open source or private model. However, the permissionless and composable nature of blockchain data encourages more rapid and open developer experimentation, which one must believe will ultimately result in richer end experiences for users.

As developer bases become more distributed and users traverse platforms more freely, value flows become much more complex and difficult to orchestrate. For developers, contributions become more granular and shared between more parties. For users, identity and inventory become increasingly fragmented. Distributed parties and information are one of the key trade offs of decentralization. In order to resolve these issues, data must adopt stronger provenance and coordination features–to both ensure verifiability and accountability of information and seamlessly orchestrate information and value flows between parties across these decentralized bases.

While the means by which permissionless, composability, provenance, and coordination affect users are more nuanced, the value of ownership and autonomy appear more clear.

In web3, whatever you own onchain, you own everywhere, forever.

However, as I outlined earlier, ownership and autonomy are contextually valuable.

Ownership of private and identifying information like PII and highly-secure assets are always important to users, but consumer social platforms are most powerful when they create new value substrates for users to own. I cannot stress enough that value does not have to be explicitly financial.

To steal a few excerpts from Eugene’s canon piece “Status as a Service (StaaS)”:

“Let's begin with two principles: People are status-seeking monkeys. People seek out the most efficient path to maximizing social capital”

“We have no such methods for measuring the values and movement of social capital, at least not with anywhere near the accuracy or precision. [...] Despite this, most of the social media networks we study generate much more social capital than actual financial capital [...] And, while we may not be able to quantify social capital, as highly attuned social creatures, we can feel it. Social capital is, in many ways, a leading indicator of financial capital, and so its nature bears greater scrutiny. Not only is it good investment or business practice, but analyzing social capital dynamics can help to explain all sorts of online behavior that would otherwise seem irrational. [...] What ties many of these explanations together is social capital theory, and how we analyze social networks should include a study of a social network's accumulation of social capital assets and the nature and structure of its status games. In other words, how do such companies capitalize, either consciously or not, on the fact that people are status-seeking monkeys, always trying to seek more of it in the most efficient way possible?”

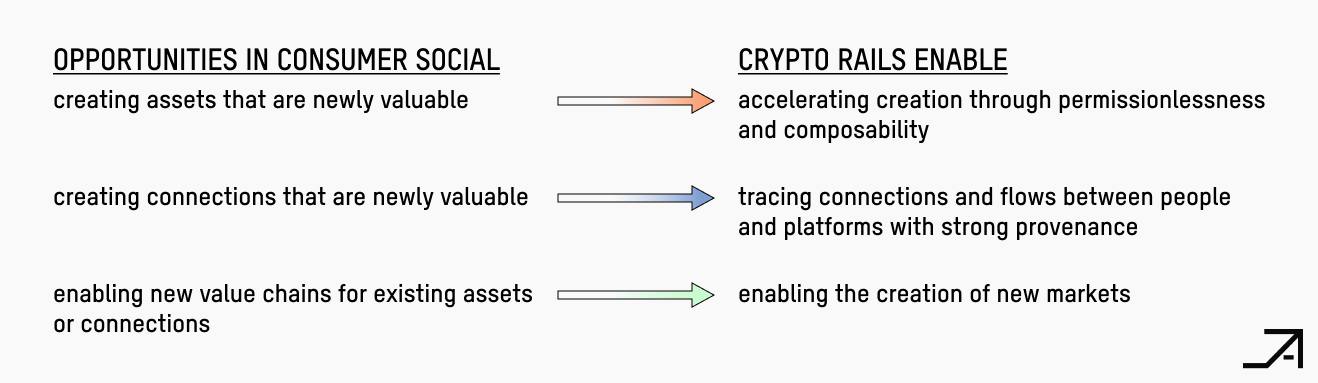

My interpretation of these specific quotes is that humans are generally very good at finding ways to increase and leverage their own social capital. The opportunity for new consumer social platforms therein lies in either 1) creating assets that are newly valuable, 2) creating connections that are newly valuable, or 3) enabling new value chains for existing assets or connections.

Tying this more meta-point to crypto, crypto is uniquely good at 1) accelerating creation through permissionlessness and composability, 2) tracing connections and flows between people and platforms with strong provenance, and 3) enabling the creation of new markets.

What has hopefully become clear through this exploration, is that creating new, sustainable value mechanisms is much more complex and nuanced than assigning a speculative dollar value to an asset. This is not all to say that financial capital is not an important lever for social experiences. Financial speculation and gambling can be very fun and very lucrative. Wealth will likely continue to be *the* status marker for a very long time. Creators should be able to directly channel social capital into financial capital. Creating new, sustainable value mechanisms also requires reaching beyond theoretical principles like “permissionless” and “composable” as means to reach users.

History tells us that the most paradigm-shifting markers for value originate not from dollar value or grandstanding, but from new experiences demanded by concentrated movements of people (often underserved) with new interests and new tastes.

I’m most excited about a future that uniquely enables new means of creative expression and value distribution. This future is already rapidly approaching. Creation is easier, faster, and more distributed than ever before, thanks to the globalizing force of the internet and more emergent technologies like AI, and people’s identities, connections, tastes, and interests are also increasingly more complex and distributed.

Onchain mechanisms are uniquely positioned to unlock collaboration, power experimentation, and ultimately track and create value for builders, creators, and users–all while maintaining user sovereignty.

At the beginning of this post, I mentioned a post on my personal blog about the state of the music industry. At the end of that original post, I proposed a few new models for tools for artists and social platforms more broadly that I would love to see come to life:

“Platforms that spotlight a track’s social provenance, highlighting its often unsung songwriters and producers, and create rich attribution graphs and experiences around those social connections.

Platforms that spotlight a track’s data provenance, gamifying remixing and experimental AI creation while preserving attribution and data provenance.

Decentralized media and curatorial platforms, where media is sustainably co-created and co-distributed by the local scenes and communities that create niche scenes and sounds.

Digiphysical platforms and experiences that sit at the interplay of live and digital.”

I’m more confident than I ever have been that the rails of these next-generation platforms and many more will live onchain.

Thank you to Eugene Wei, Reggie James, Andy Weissman, Seyi Taylor, and Ruby Justice Thelot for thoughtful and critical review and feedback on drafts of this post.

Thank you to Jacob Horne, Yancey Strickler, and Josh Benaron whose pieces I referenced in this post.

Disclaimer:

This post is for general information purposes only. It does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any investment and should not be used in the evaluation of the merits of making any investment decision. It should not be relied upon for accounting, legal or tax advice or investment recommendations. You should consult your own advisers as to legal, business, tax, and other related matters concerning any investment or legal matters. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by Archetype. This post reflects the current opinions of the authors and is not made on behalf of Archetype or its affiliates and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Archetype, its affiliates or individuals associated with Archetype. The opinions reflected herein are subject to change without being updated.